"WHAT'S IN YOUR CART?" is an interview series where we invite record-loving guests to choose '5 Records They Want Right Now' from the ELLA ONLINE STORE lineup.

This edition’s guest is Kaoru Inoue, an artist who has continued to create a uniquely refined, hybrid aesthetic under both his own name and his Chari Chari moniker, captivating music lovers far beyond the realm of dance music since the 1990s. Presented here as a special double feature alongside “After Hours Session (AHS)”, where he delivered a rare, vinyl-only Post Punk & New Wave mix.

Even with the excitement of his DJ set still lingering, the five “records he wants right now” that Inoue selected from the shelves of ELLA RECORDS VINTAGE are quintessentially his—intelligent, aesthetically sharp, and subtly radical, echoing the sensibility of his AHS session.

For this feature, the interview section is also divided into Part 1 & Part 2.

Part 1 covers AHS and Inoue’s musical journey, while Part 2—true to the spirit of What's In Your Cart?—dives into his deep love for records. Please enjoy the full story.

Interview & text: Mikiya Tanaka (ELLA RECORDS)

Photo: Hiraku Noda (ELLA RECORDS)

Furniture design & production, Interior coordination: "In a Station"

Special thanks to: Satoshi Atsuta

Kaoru Inoue's “5 Records I Want Right Now”

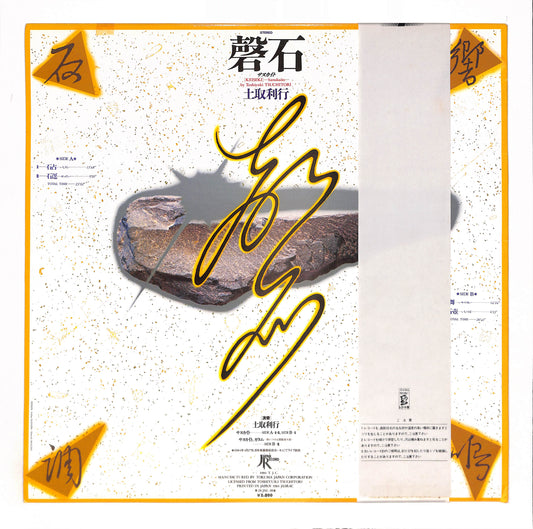

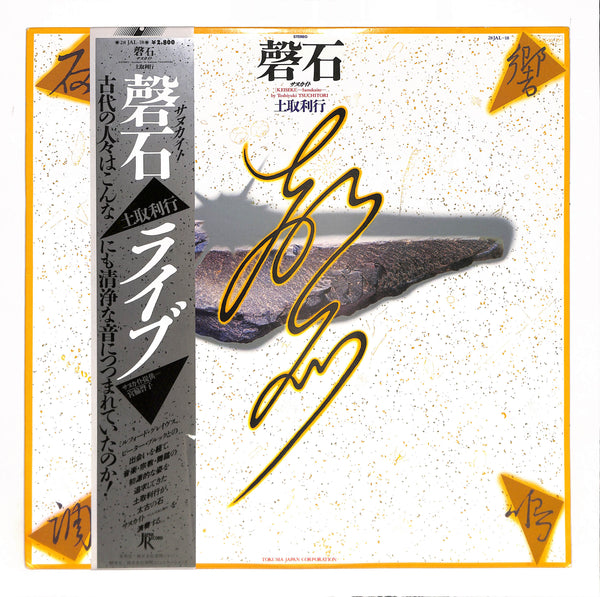

①Toshiyuki Tsuchitori / Keiseki -Sanukaito-(1984)JPN original

Back in ’91, for about four years, I was DJing while also working as a world-music buyer at WAVE, the large record store that used to be in Roppongi. One of my senior colleagues there curated this fascinating section that brought together so-called New Age records and CDs, along with things like crystals and crystal bowls. That’s where I first came across Tsuchitori’s music, and it immediately caught my interest.

Tsuchitori is a rather unusual kind of musician—he conceptually recreates the sounds of the Jōmon period. From a world-music perspective, that primitive quality really drew me in, and I also loved the mix of what we’d now call a “spiritual” vibe, a bit mysterious, a bit academic. It felt cool. But it wasn’t until later, when I started digging into more experimental music on my own, that I realized, “This guy is seriously next-level.”

He’s still active today, and although I own a fair number of his works on CD, including recent ones, I don’t have many on vinyl because they’re expensive. This one is the title you see most often, but still a bit pricey, so I haven’t managed to pick up the record. I’d love to read the liner-note insert, and honestly, as a record lover, just seeing the jacket makes me want to own it.

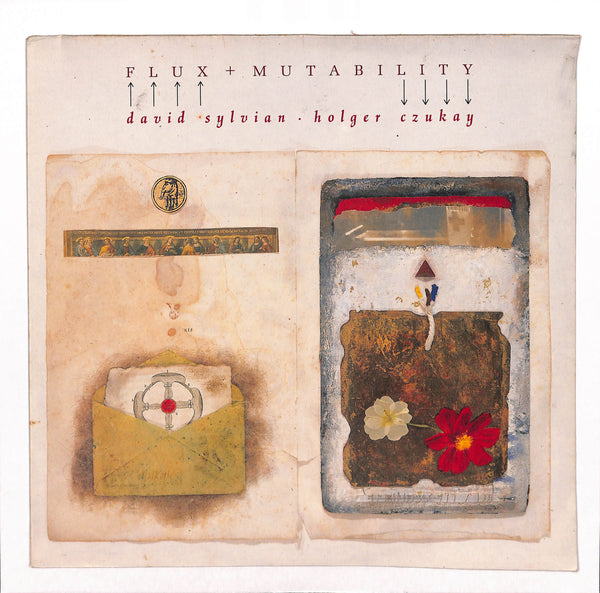

②David Sylvian and Holger Czukay / Flux + Mutability(1989)EU original

I really love both David Sylvian and Holger Czukay. With Sylvian, it’s not just his vocal tone—I’m also a big fan of that uniquely funky sound he developed in the later years of Japan, and I absolutely love the ambient direction he took in his solo work, like Gone to Earth (1986).

As for Czukay, since I’m someone who creates music not so much with instruments but with samplers and a computer-based setup, the way he constructs sound has actually been a huge reference point for me. From that angle as well, he’s an artist I’ve admired for a very long time.

This record is one of their collaborative works, and they released another with a similar concept, Plight & Premonition (1988). Both are, broadly speaking, ambient-oriented pieces. But this one came out right around the time when the world was shifting from vinyl to CDs, so you hardly ever see it on vinyl. I’m guessing it wasn’t pressed in large quantities. I also love that there’s one track per side—that’s a big plus for me. This is definitely one of the records I truly want today.

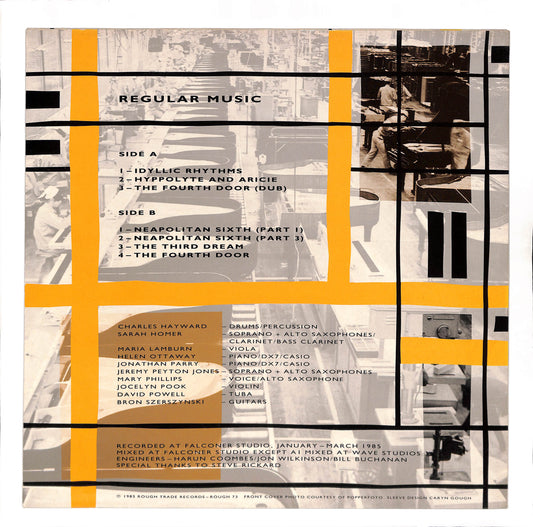

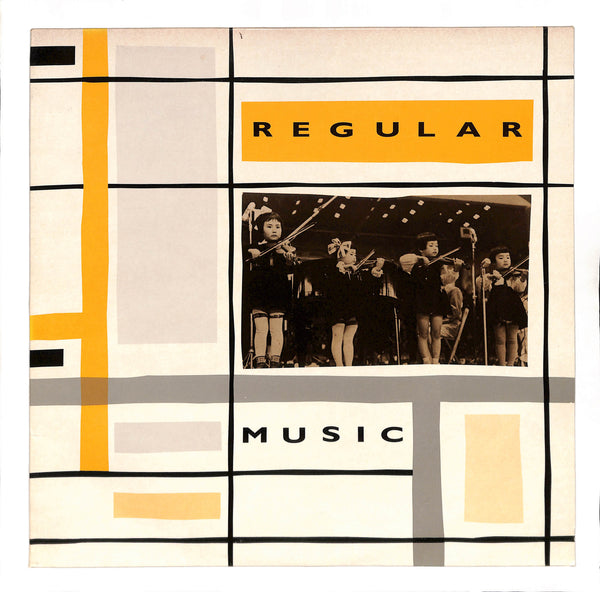

③Regular Music / S.T.(1985)UK original

This is an artist I don’t think many people know. They make a kind of electronic minimal music that feels like it comes from a Philip Glass–style classical lineage, and as far as I know, they only released one record on Rough Trade. I’m really into post-punk and new wave—so much so that I’d say it’s one of my musical roots—but I had absolutely no idea about this artist at the time. I’m pretty sure I stumbled across them by chance in my thirties while digging into that era.

Looking at the jacket now, I noticed that the top credit in the lineup is Charles Hayward from This Heat. I’m a huge This Heat fan, so that was probably how they first came onto my radar. I thought this might be one of those records you could pick up cheaply, but it turned out to be surprisingly hard to find. I actually first heard it only when it was reissued on CD. So this is definitely something I’d love to own on vinyl as well.

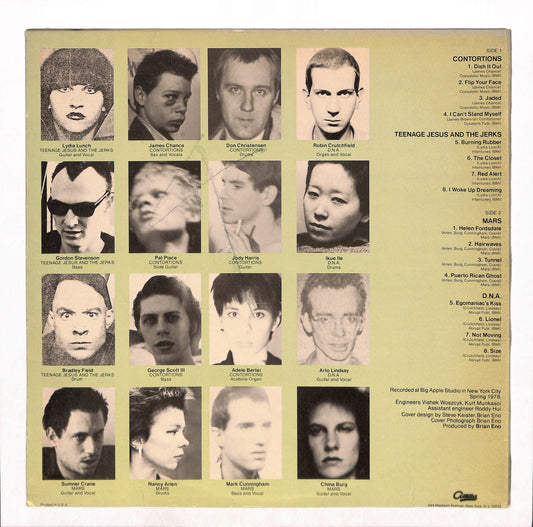

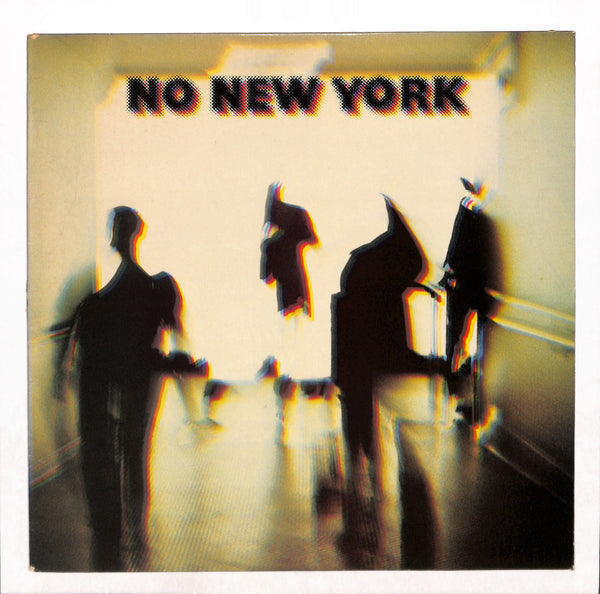

④V.A. / No New York(1978)US original

No New York might seem like the kind of record people would assume I’ve listened to thoroughly, but surprisingly, I actually hadn’t. When I was a teenager, punk was my gateway into British music, and from there I dove into Japan’s underground punk scene and practically lived in live houses. In other words, at that time I had almost no exposure to things like New York punk.

After becoming a DJ, I did play disco-oriented No Wave bands like Konk and Dinosaur L, but I barely touched the core No Wave stuff. Even with No New York, which is considered a classic, I bought the CD at some point but mostly left it sitting on the shelf. But the producer of this record is Brian Eno. And Eno has always been a deeply fascinating figure for me. I absolutely love Talking Heads—their white funk sound infused with Eno’s ambient sensibilities. Because of that, No New York has become a record I now genuinely want to own, especially from the perspective of exploring Eno’s production work.

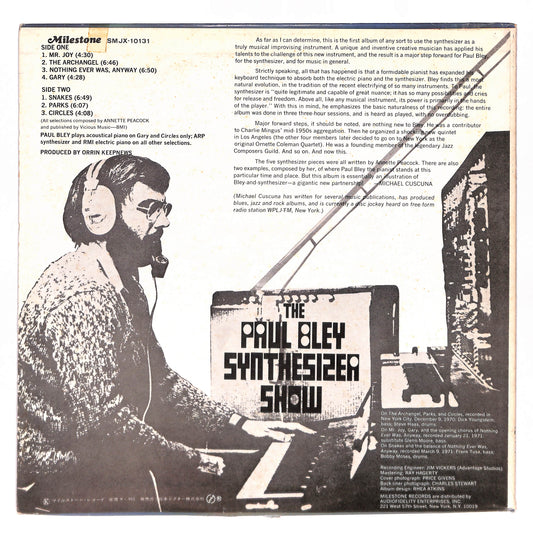

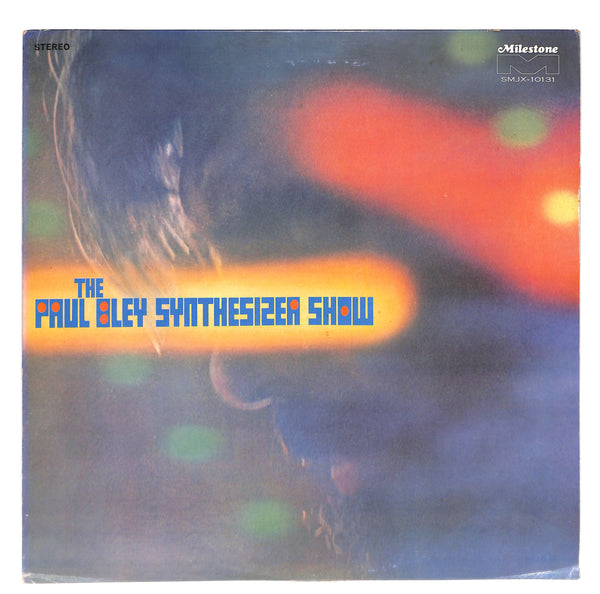

⑤Paul Bley / The Paul Bley Synthesizer Show(1971)JPN pressing

I got into DJing in my twenties through acid jazz, so I’ve loved jazz ever since those days—but I actually discovered Paul Bley only recently. Six years ago, CHEE SHIMIZU opened his shop “PHYSICAL STORE” in Shimo-Igusa on the Seibu Shinjuku Line, and as I started stopping by on my walks from home, we gradually became close. At some point we decided to host a listening party at the shop, with just the two of us selecting music. Late into the night during that session, CHEE played Ballads, one of Bley’s early ECM releases. It was the kind of music where you can sense the shared elements between free jazz and contemporary classical, and it hit me deeply at that moment. The contemporary-classical-leaning piano, joined by drums and bass, creates this feeling of rhythm moving within some vast, slow cycle, even though there’s no fixed groove. And Bley’s piano itself has this almost erotic, perversely alluring quality—utterly unique.

After that, I fell completely into Paul Bley’s music and bought quite a lot of his records. This album is one of the works from the early ’70s, during the short period when he was experimenting with synthesizers. I own it on CD, but seeing the vinyl makes me want it all over again. I really enjoy reading the liner notes from that era, so the Japanese pressings are especially appealing to me.

Interview Part 1: Tracing the Origins of Kaoru Inoue’s Sound

As this feature is presented in two parts, Part 1 begins with a conversation about After Hours Session, leading into Inoue’s musical background and how it has evolved over the years. Punk, acid jazz, world music, and eventually contemporary Japanese music—our discussion blossomed into a deep dive through many layers of his musical journey.

━━Thank you again for the fantastic DJ set on AHS earlier. A post-punk mix from you feels like something quite special. What was the theme of your set this time?

Inoue: I’ve watched a number of other AHS sessions, and many of the younger DJs were playing house. So I thought it might be interesting to try something a little different. I figured it would be nice to introduce “the sound of my generation” to younger listeners. So I put together a set centered around the post-punk and new wave from the UK, Europe, and Japan that I loved almost in real time, then mixed in some of the funkier tracks I started playing after becoming a DJ. These days I hardly ever do dance-oriented DJ sets strictly on vinyl, and since this was a rare opportunity with filming involved, I practiced like crazy at home last night (laughs).

━━Personally, I’ve always felt that ever since the Chari Chari days, your music has carried a kind of post-punk spirit beneath the surface—an edge, a refined radicalism, an artistic sharpness. So when today’s DJ set turned out to be a full-on post-punk set, I secretly thought, “I knew it!” and couldn’t help but feel delighted.

Inoue: I’m really happy to hear that. My musical starting point was YMO back in junior high, but in high school—as I mentioned earlier—I started playing guitar in a band. When I was 17, a classmate invited me to join a hardcore punk band. I grew up in Sagami-Ono in Kanagawa, so we often played at live houses in Yokohama. The scene was full of intimidating hardcore seniors (laughs). I ended up absorbing a lot from their attitude, and also from the punk spirit of someone like John Lydon (Johnny Rotten) of The Sex Pistols—this idea of “saying no to everything!” As you grow older, that kind of stance gets tempered, of course, but I think a part of it has stayed with me. I don’t go around saying “No!” anymore though (laughs).

━━You first went through punk, and then later found yourself deeply immersed in acid jazz. At first glance that might seem a bit ambivalent, but what sparked that shift for you?

Inoue: Acid jazz, put simply, was a culture in London—championed by Gilles Peterson—of “dancing to jazz.” And around 1989, when I was a university student, there were people in Japan who were trying to bring that culture here. I had friends who were already DJing who told me things like, “Acid jazz is insane right now,” so I naturally became curious. While still playing in my band, I started helping out at events thrown by those people. They happened to need someone who could drive a 4-ton truck to transport the event decorations, and since I had a driver’s license, they asked if I wanted to give it a try. I accepted without hesitation.

━━So you actually took part as a truck driver?

Inoue: That's right. I delivered the deco to Club Citta in Kawasaki, and I got to see the event on-site. If I remember correctly, the DJ was Tadashi Yabe—before he formed U.F.O. He was spinning fast, swing beat jazz, and the London dance crew called I.D.J. (I Dance Jazz) was dancing to it. They were incredibly stylish, doing these acrobatic moves. It totally blew me away. Watching a DJ play records, people dancing, and the whole place getting fired up… After witnessing that, what I was doing—playing in a Japanese-language rock band—suddenly felt uncool to me (laughs). So I quit the band and gradually started aiming to become a DJ.

━━Then in 1994 you released music as Chari Chari. Rather than straightforward four-on-the-floor dance music, you had already begun establishing a hybrid sound that incorporated ambient and tribal elements. When you began creating your own music, where did that direction come from?

Inoue: I think the encounter with the sampler was huge. After quitting the band and wanting to make my own tracks, I was listening to Jungle Brothers and Soul II Soul, and their approach—creating music through sampling—completely shocked me. Back in my band days, I used to write songs on guitar, but I’m the type who wants to handle the arranging myself as well. And when you try to do all that and start giving instructions to the members, they find you incredibly annoying (laughs). Working alone meant I didn’t have to deal with that kind of hassle, so I bought a sampler and a single synth.

━━When you first bought your sampler, what kind of music did you start sampling?

Inoue: What I wanted to try first was expressing exotic music over breakbeats. At the time, I was really into traditional Indonesian music. Gamelan is the famous one, of course, but Indonesia actually has many different forms of traditional music. I wanted to hear them locally, so I went there for the first time in my junior year of university, and then four or five more times throughout my twenties. There’s this sense of Asian exoticism—parts that are completely different from Japan, yet somehow share an underlying connection. I thought it would be interesting to fuse that kind of sensibility with breakbeats.

━━At the time, were there any other musicians making that kind of music?

Inoue: I don’t think there were. And that’s exactly why I wanted to try making it myself. I remember feeling a real sense of excitement—like I was creating something new as I worked on it.

━━In terms of exoticism, weren’t your experiences from your time at WAVE also significant?

Inoue: Absolutely. I actually joined WAVE after seeing a job listing in a music magazine. At the time, the world-music buyer at the Roppongi store was Takashi Harada—now of EL SUR RECORDS. I had been reading his writing in Music Magazine, so I already knew I wanted to work under him if I could. Luckily, I was also assigned to the Roppongi store, and after spending the first six months in charge of jazz, I was transferred to the world-music section.

━━Roppongi WAVE is still remembered as a legendary store at the forefront of music culture at the time. Before the internet, how did you develop the instincts to source world-music records?

Inoue: In short, I approached it from a DJ’s perspective. The world-music section naturally dealt with music from all over the globe, which included, for example, pop music from places like Hong Kong and Taiwan, along with the fans who sought those titles. And since the CD era had already arrived, it wasn’t possible to shape the entire section purely through a DJ lens. So while I made an effort to study and meet those basic needs, the store also constantly expected us to create more proposal-driven displays—what would now be called “curation.” That’s where I tried to bring in my own DJ-oriented perspective.

━━Are there any specific projects from that time that you still remember clearly?

Inoue: I remember creating a section themed around “Music of the Mediterranean.” I grouped together Spanish music, Greek music, Tunisian Arab music, and so on, adding signage and handwritten comments—partly driven by a bit of my own fantasy that there might be some Balearic common thread running through them. And when customers actually bought those recommendations, it made me genuinely happy. World music is full of the unknown, so I was always discovering new things myself and really enjoyed the work.

━━Learning about world music sounds like it would naturally deepen your understanding of global cultures and historical contexts as well.

━━Learning about world music sounds like it would naturally deepen your understanding of global cultures and historical contexts as well.

Inoue: Definitely. In fact, there was a period when I was working at WAVE while also writing as a freelancer. I've always had this researcher-type mentality—I genuinely enjoy looking things up. So I dug deeply into folk and traditional music too. In that world, understanding the cultural and historical background behind the music is essential, and immersing myself in that was incredibly exciting for me.

━━In creating your own music, did you ever find yourself being cautious about sampling folk or traditional music?

Inoue: Respect for the source material was always the baseline, but beyond that I tried to find my own balance between strictness and a more casual approach. Back then, Music Magazine was actively championing folk and traditional music, and its editor-in-chief, Toyo Nakamura, often delivered sharp critiques about cultural appropriation—especially when white musicians approached folk traditions. I was heavily influenced by that discourse. So when making my own music, I was always conscious of not taking the easy way out. That said, it ultimately comes down to my own sense of balance. Some people might have felt, “This method is unacceptable.” Still, if I was going to do it, I wanted to engage with the material deeply enough—not to claim it as my own, that would be presumptuous—but to at least reach a point where I could confidently present it as my music.

━━In your recent works, you’ve also begun exploring contemporary Japanese traditional music. Would you say that this, too, is an extension of your long-standing interest in world music?

Inoue: That actually started after I began visiting CHEE’s shop, PHYSICAL STORE, so it’s a relatively recent development. At some point, he and I became close enough that whenever I visited the shop, we’d just sit around for hours, drinking coffee and chatting. And maybe four or five years ago, the topic of “contemporary hōgaku (Japanese traditional music) is incredible, isn’t it?” came up. The conversation kept building from there, and soon we found ourselves talking about Japanese contemporary composers—especially how extraordinary Toru Takemitsu is. From then on, we began regularly sharing our new discoveries with each other, and eventually that evolved into a talk event at his shop. It was like a presentation of our research—introducing Japanese contemporary music and contemporary hōgaku while playing records (laughs). But people actually came, and it turned into something real.

━━What do you find most compelling about contemporary hōgaku?

Inoue: The easiest example of what drew me in is the koto. For instance, there are players who approach the koto in a highly contemporary, almost minimalist way, or performers who use the lower registers of the sanjūgen—a 30-string koto—striking it almost like percussion to produce these incredible low frequencies. I’d always liked gagaku, but discovering that there was a completely different world outside that framework opened things up for me. From there, I became fascinated by the blend of traditional and contemporary approaches in Japanese music.

Around that same time, I also met the koto player Kohsetsu Imanishi at an outdoor ambient festival, which was another major turning point. She’s doing this remarkable work that you could call “contemporary–contemporary hōgaku,” and she told me she was very interested in the kind of contemporary Japanese music that DJs pay attention to. She even came to the talk event I mentioned earlier. We became friends and have talked about recording together someday—though we haven’t managed to make it happen yet.

━━Having explored so many forms of folk and traditional music over the years, did approaching contemporary hōgaku also come from a desire to rediscover some kind of distinctly Japanese expression or identity within your own work?

Inoue: The idea of presenting my identity as a Japanese artist through my music is something I actually started thinking about back in my twenties. But at the time, I didn’t really know how to do that within the context of club music. The only attempt I made was a track where I sampled gagaku and turned it into a kind of breakbeat piece. There was a period when I was very conscious of cultural identity—not in a political sense, but in terms of aesthetics. These days, though, my mindset is much more neutral. I’ve realized that there are actually many ways I can work together with traditional instruments and performers quite naturally. Collaborating with Kohsetsu Imanishi is one of those possibilities, and I really hope to develop more of that going forward.

━━I would absolutely love to hear that someday. I’m looking forward to it.

Inoue: I’ll do my best.

Interview Part 2: Kaoru Inoue and Record

Shifting gears from Part 1, the latter half of the interview takes on a more relaxed tone as we explore Inoue’s personal relationship with records. Enjoy this glimpse into his pure, die-hard love for vinyl.

━━How often do you go record shopping these days?

Inoue: Probably about once a week. That’s roughly how often I have a fully free day to enjoy some time to myself. Recently, I’ve gotten into taking long walks across the city. I like heading out early, grabbing lunch somewhere, and visiting a museum. And along the way, there are always neighborhoods where record shops are clustered together. So I make sure my walking routes include a few record stores.

━━Do you have any favorite routes in particular?

Inoue: The one I’m most into right now starts at the National Museum of Modern Art in Takebashi. I’ve recently gotten really interested in modern art. So I’ll walk from there to Jimbocho, grab something to eat, then continue on to Ochanomizu and check out Disk Union. Sometimes I wrap it up there, but on a good day I’ll keep walking—through Suidobashi and all the way to Myogadani. It’s about six kilometers in total, I think. Walking through all those different kinds of buildings—whether it’s the visual clutter or the architectural beauty or the quirks of the terrain—is incredibly fun. There was a time when I preferred nature and even felt I disliked Tokyo, but now I’ve completely awakened to the charm of walking through the heart of the city.

━━How many records do you currently own?

Inoue: I’m not exactly sure. I have shelves at home that can hold about 5,000 records, and I initially tried not to exceed that—but in the end, they overflowed. Now there are records scattered in front of the shelves and in all sorts of places. From the mid-2000s, I gradually shifted my DJing to digital, so there was a period when I didn’t buy any vinyl at all. And when I moved into my current place, I actually got rid of a lot of records, so at first there was plenty of space on the shelves. But then, about ten years ago, for some reason I started buying vinyl again. Even though I regularly purge things, the collection has slowly grown… and now it’s spilling out of the shelves. In the end, hunting for records yourself is just insanely fun. You can’t stop. I don’t even know what that compulsion is.

━━What does the genre breakdown of your record collection look like?

Inoue: About 20–30% is club music in a broad sense, including ambient-leaning stuff. A little over 10% is jazz. Just under 10% is soul/rare groove. Close to 20% is made up of “obscure sounds” and experimental music that doesn’t fit neatly into any genre. Around 20% is music from around the world—mostly African, Latin, and Brazilian. Just under 10% is Japanese music, and another just-under-10% chunk is post-punk/new wave. I also have a section for things I’ve released myself or projects I’ve been involved in.

━━You don’t seem to have much in the way of classic rock, do you?

Inoue: I only really bought what you’d call “straight-up rock” when I was in junior high, and the ones I’ve kept are just a handful—The Velvet Underground to Lou Reed, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, that sort of thing. But lately I’ve started thinking that kind of stuff really is great after all, so the other day I picked up the Japanese editions of David Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy—Low, Heroes, and Lodger—which he recorded in the ’70s. Partly because I wanted to read the liner notes, and also because UK originals have gotten pretty expensive.

━━Do you have a particular attachment to original pressings?

Inoue: Honestly, not anymore. There was a time when I’d look for originals based on the country—like wanting a Dutch pressing if the artist was from the Netherlands. But I was never really interested in paying high prices for rare originals, like first-press Blue Notes. I’ve heard plenty of stories about people getting hooked after someone played them an original pressing on a really serious audio setup, so maybe it would be different if I’d had that kind of experience.

━━Are there any genres you're particularly into or actively searching for right now?

Inoue: Contemporary music in a broad sense, including modern Japanese compositions. I’ve been looking for small-ensemble, chamber-music-like pieces with restrained dynamics—things that almost play like ambient music.

And jazz, of course. As I mentioned with Paul Bley, in recent years—partly thanks to CHEE’s shop—I’ve been buying records whose jackets I’ve known forever but had somehow never actually listened to. I’ve also been consistently collecting ECM releases, and I’m still hunting for the ones I don’t own yet.

Outside of that, my interests really span a wide range, so whenever I go to a shop, I try to check as many sections as time allows.

━━What’s at the top of your current record want list?

Inoue: The top… hmm, what would it be? Let me take a quick look at my Discogs want list. I have quite a few titles saved there, but truly interesting contemporary music records are expensive.

It’s hard to pick just one, but among those pricey yet desirable records, one I really want is Slow Dance On A Burial Ground (1984) by Stephen Montague, released on Lovely Music, a U.S. contemporary music label. It’s a minimal-music-type piece with one track per side, and it’s incredibly good. I definitely want this one.

Inoue: Another one is Dance Free (1982) by Cloud Dance. I believe it became a garage/loft classic in the U.S., and it has a danceable feel with instruments like tabla. But it’s gotten insanely expensive. I remember seeing it for about ¥18,000 three years ago and passing on it, and when I checked now, it’s over ¥40,000 (laughs).

━━Have you come across any new music recently that particularly impressed you?

Inoue: There’s so much that it’s hard to choose… For example, in jazz, there’s an album called Undine (1987) by the pianist Anthony Davis. He’s a Black keyboard player who was involved in the loft-jazz scene, and I think he must have a classical background. It’s free jazz, but also very structured, with a distinctly contemporary–classical quality. I’m extremely weak for music like that—it gets me every time.

Another one is the Paul Motian Trio’s It Should Have Happened Long Time Ago (1985), released on ECM. I recently bought it on vinyl and listened to it for the first time, and it was amazing. To be honest, a lot of jazz from the ’80s can be pretty dull, but ECM is consistently fascinating.

Inoue: Looking back like this, I realize I actually buy a fair number of records myself (laughs). I just really love records—there’s something magical about them. What is that magic, I wonder?

━━Let me ask you the opposite: what do you think it is?

Inoue: It’s hard to sum up in a single word, but one thing is definitely the artwork. I love visual art—especially painting—so maybe I sense a connection between records and two-dimensional art. The size of a record jacket just feels perfect, and I can’t help but be drawn to it.

Another thing is emotional attachment. Ever since my teens I saved up my allowance to buy records, but because I never had enough money, I often rented them and dubbed them onto cassette tapes. Now, as an adult, there’s also the joy of slowly collecting on vinyl all the records I couldn’t afford back then—and that naturally comes with a sense of nostalgia.

So perhaps records are something that can ignite all kinds of emotions: the excitement of discovering the unknown, nostalgia, the urge to collect. And on top of that, there’s the thrill of the hunt. You go to a record store, lose track of time flipping through crates, and even if you end up not buying anything, just looking is fun in itself, isn’t it?

━━What makes a “good record shop” for you?

Inoue: Let me think… First, a place that isn’t bound by genre. A shop where the selection is curated with real depth rather than just superficially. And a shop owner who is insanely passionate about music, yet still able to have a good conversation. Maybe those old-school, intimidating store owners don’t really exist anymore, but it’s great when you can ask a question and they respond warmly—share their knowledge, play things for you, that sort of thing. But honestly, I think every record store has its own charm, and I find myself wanting to visit all kinds regularly. In the end, I just love record shops as a whole.