"WHAT'S IN YOUR CART?" is an interview series where we invite record-loving guests to choose '5 Records They Want Right Now' from the ELLA ONLINE STORE lineup.

Our guest this time is Takuro Okada—a songwriter, guitarist, and producer whose multifaceted talents have earned him recognition as one of the key young figures in Japan’s current music scene. A dedicated music enthusiast and well-known vinyl lover, Okada has been a regular user of ELLA RECORDS, which we deeply appreciate.

During his visit to ELLA RECORDS VINTAGE, his eyes lit up as he browsed the shelves, exclaiming, "I’ve always wanted to come here!" However, selecting records proved to be a real challenge, as he humorously described it as "as tough as a trolley problem" due to the sheer number of tempting options.

Alongside a thought-provoking interview that reveals his deep and sincere approach to music, enjoy Okada’s carefully chosen “Five Records of Agonizing Dilemma.”

Interview & text: Mikiya Tanaka (ELLA RECORDS)

Photo: KenKen Ogura (ELLA RECORDS)

Furniture design & production, Interior coordination: "In a Station"

Special thanks to: Satoshi Atsuta

Takuro Okada's “5 Records I Want Right Now”

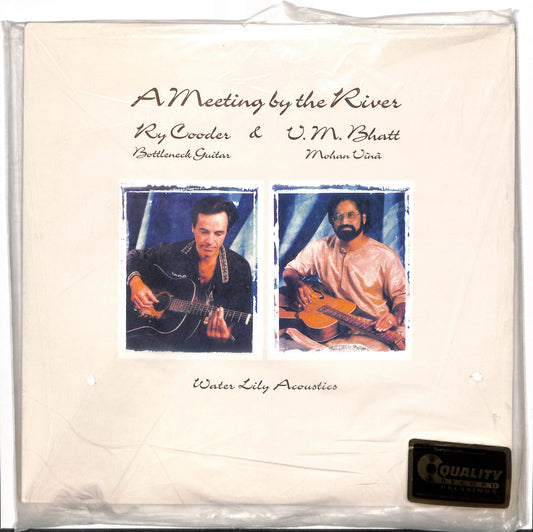

①Bobby Hutcherson / Components(1966)Stereo/US original

This is my favorite Blue Note record. To be honest, I hadn’t really listened to much Blue Note until recently. I’ve always loved jazz—back in high school, as a guitar kid, I listened to a lot of Grant Green, Kenny Burrell, Barney Kessel, and Jim Hall. Later on, I got into avant-garde guitarists like Marc Ribot, free jazz figures like Sonny Sharrock, and improvisers like Derek Bailey. I also became hooked on ECM records. For about the last decade, I was mainly collecting those kinds of jazz records.

But recently, something changed. Earlier this year, I suddenly got really into Ras G. Until then, I didn’t feel much of a connection between the music I made and hip-hop. However, when I read a book about J Dilla, I realized there were aspects of his approach that resonated with what I wanted to do musically. That led me to explore J Dilla, Madlib, and especially Ras G, which rekindled my interest in jazz within the context of Black culture. I realized I hadn’t properly explored Blue Note records beyond the guitarist-led ones, so I started diving into them this year. These days, whenever I step into a record shop, I go straight to the Blue Note section (laughs).

Right now, I find myself drawn less to hard bop and more to what’s called the “New Mainstream” or post-bop movement—artists like Bobby Hutcherson and Andrew Hill. Their music has a modal foundation but also a chamber music-like quality. It’s distinct from ECM but occasionally leans into an ambient-like space. This Bobby Hutcherson album, in particular, stands out to me. Hutcherson is one of those musicians who strikes an incredible balance. The unique qualities of the vibraphone—its quiet, cool tone—contribute to this balance. He doesn’t veer too far into free jazz, isn’t overly modal, nor excessively spiritual. There’s a restrained intelligence in his music, yet his playing carries a physical passion. It’s a perfect equilibrium.

Incidentally, the first Blue Note CD I ever listened to was Grant Green’s Idle Moments (1965), which I loved even back then. Only this year did I realize that the vibraphone on that album, which I’d always admired, was actually Bobby Hutcherson.

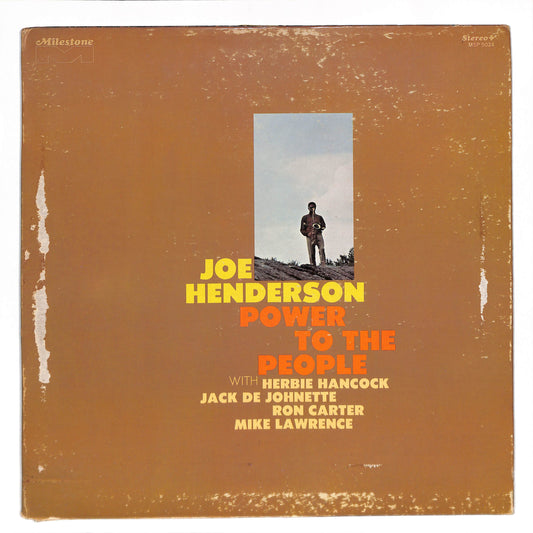

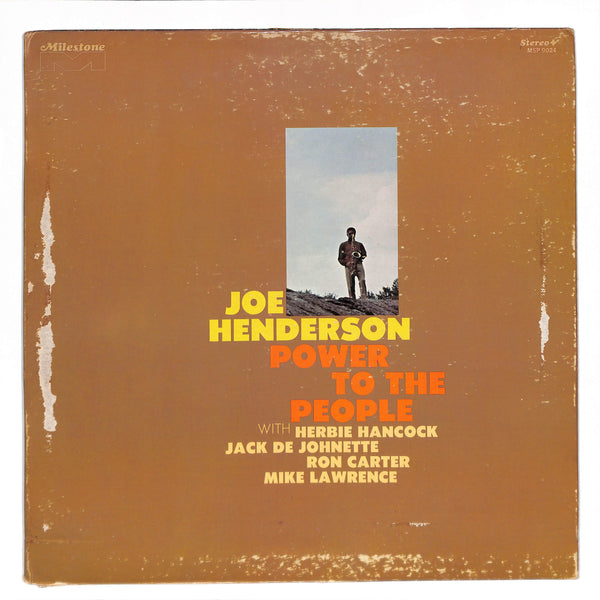

②Joe Henderson / Power to the People(1969)US original

Until this year, I’d never listened to a single Joe Henderson record. I feel like I might get scolded for saying this, but based on his name, I had this unfounded assumption that he was in the same vein as Lou Donaldson or Stanley Turrentine—more soul jazz-oriented (laughs). While I like soul jazz, it’s not something I’ve been driven to collect deeply. Then, earlier this year, as I was diving into Blue Note records, I listened to Mode for Joe (1966) and thought, “Wow, this is something special.” That’s when I really took notice of Joe Henderson. I also realized he played on Idle Moments, which made me think, “Oh, I loved that saxophone!” It all connected for me at that moment.

Joe Henderson is such a unique player. In the 1960s, there might be clear lineages of saxophonists influenced by giants like John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, or Stan Getz. But Joe Henderson felt distinct from those schools. His tone immediately stands out. He’s not overly technical, nor is he playing groundbreaking harmonies, but there’s something deeply compelling about his sound. I hesitate to describe it as “bluesy,” but it does have that kind of emotional resonance.

While his Blue Note era is fascinating, I’m currently really interested in his later Milestone years, particularly his albums from 1968 to the 1970s, where he explored more spiritual and jazz-funk territories. Power to the People is one of those records. It includes a track called “Black Narcissus,” which has this chamber music-like quality but also an Afro-centric groove, with an incredible melody. That said, I haven’t listened to the entire album yet—because this is a record I really want to own, I’m saving the full experience for when I get my hands on it.

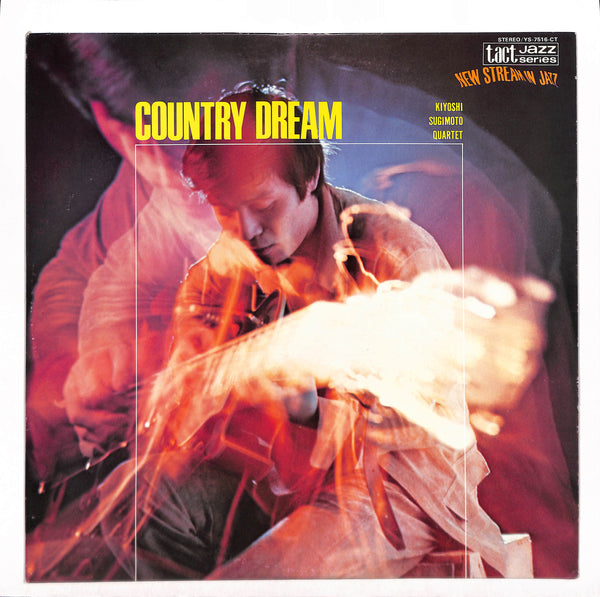

③Kiyoshi Sugimoto Quartet / Country Dream(1970)JPN original

As a musician who creates my own music, I often think about what kind of relationship Japanese people should have with Black culture. When the New Mainstream players emerged on the American jazz scene, I found myself wondering what Japanese jazz musicians of the time were thinking and creating in response. This year, researching that became one of my hobbies, and this album turned out to be the most fascinating discovery.

Back then, I think very few guitarists— even in the West— successfully interpreted the New Mainstream sound in real time. The most notable examples would be John McLaughlin and Larry Coryell, but they leaned heavily on rock idioms. I’ve explored quite a bit, and the guitarist I personally think hit closest to the mark was Ray Russell from the UK, though his work can be a little too subdued, almost lacking in excitement—though I do appreciate that about him too (laughs). Against that backdrop, Sugimoto-san’s record is remarkable. It’s simple yet rich with modal harmonies that don’t veer too far into rock territory, and it conveys a catchy sense of “jazz as dance music.” I found it fascinating that there was a Japanese guitarist at the time interpreting the New Mainstream sound in this way. There’s a unique quality to his playing that I haven’t found in other guitarists.

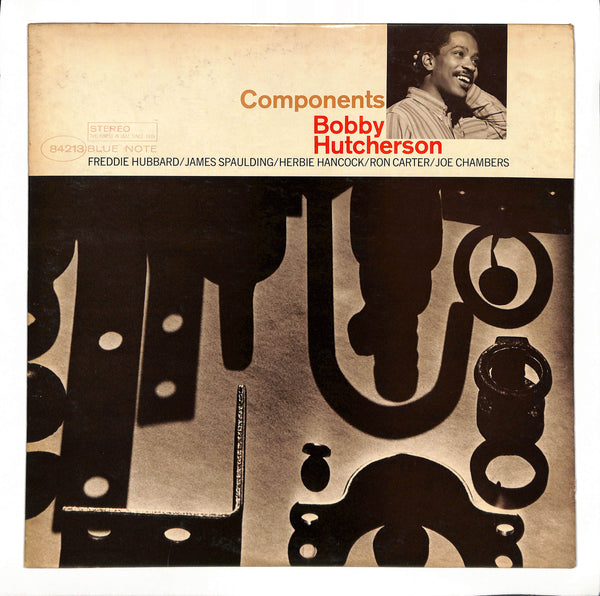

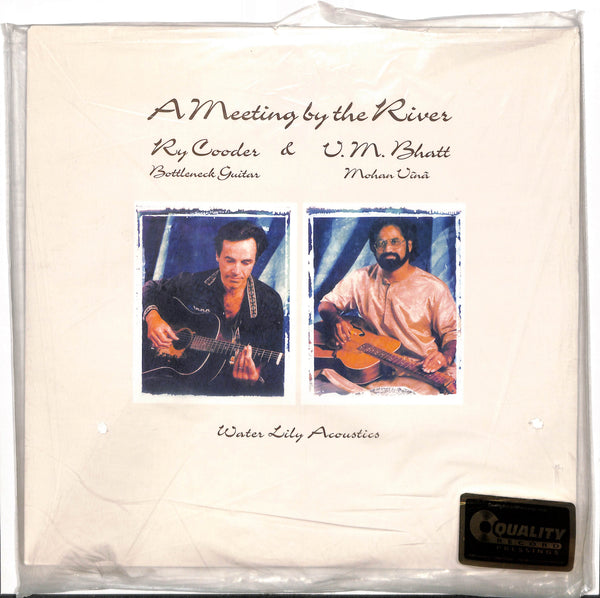

④Ry Cooder & V.M. Bhatt / A Meeting by the River(1993)US issue

I really respect Ry Cooder’s approach of not just incorporating other cultures into his music but immersing himself in those cultures. This album is a great example from the period when Ry was actively exploring non-Western music. V.M. Bhatt plays the Mohan Veena, a slide guitar he developed with a sitar-like resonance, and it’s fascinating to hear Ry’s slide guitar blend with that distinctly Indian sound. What’s remarkable is how these two entirely different musical cultures meet naturally without compromising their unique characteristics. The drone-based, single-chord structure of Indian raga aligns structurally with the open-tuning slide guitar traditions of American music. This album feels like a practical realization of that overlap.

The Water Lily label has released many other interesting projects, including Ry’s Hollow Bamboo (2000), where he collaborates with an Indian flutist, and Jon Hassell’s Fascinoma (1999), an album where he reinterprets Duke Ellington. Both are favorites of mine as well.

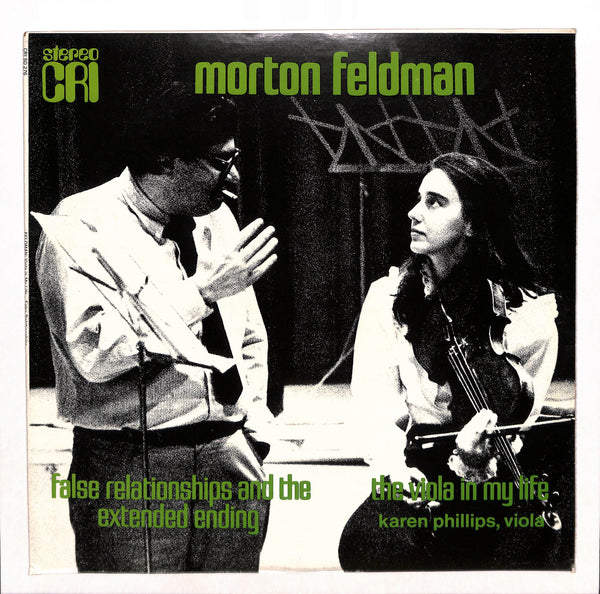

⑤Morton Feldman / Viola in My Life/False Relationships(1971)US issue

Interview: Takuro Okada and Record

━━First, since you struggled a lot to narrow it down to five records, let's shine a light on the ones that unfortunately didn't make the cut (laughs). What other records were in the running?

Okada:One of them is the US original pressing of Ralfi Pagan's With Love. It's Latin soul from Fania, but I really like the mellow cover of Bread's "Make It With You" that's on there.

There were also various original pressings of John Fahey records. In particular, I might have never seen an original of Blind Joe Death or some of the early Takoma Records releases. The cover with just the type, along with the overall presence of those records, is incredible.

Also, I've been looking for a near-original stereo pressing of John Coltrane's A Love Supreme. I don't need the complete original, but something close to it, in terms of both condition and price. I've been searching for it for a while.

━━Mr. Okada, you also covered A Love Supreme on your album Betsu No Jikan (2022). Is it a work that holds a special place for you?

Okada: Yes, definitely. This album is considered a masterpiece among jazz records, so I first heard it fairly early on in my teenage years, while I was also listening to hard bop classics like Sonny Rollins' Saxophone Colossus and Miles Davis' Cookin'. From the very beginning, it sounded completely different from anything I had heard before, and I was really shocked when Coltrane’s whispers started coming in during the track. It made me realize for the first time that there’s a world in music that doesn’t involve singing well or poorly. But even with that, it’s still catchy, and I found myself humming the riffs while making dinner (laughs). So, honestly, I’m not sure if I actually like the album or if I truly understand it, but since then, it’s definitely become one of those records that I just can’t get out of my head.

━━Speaking of jazz, earlier in your conversation about Kiyoshi Sugimoto, you mentioned the topic of “the distance between Black culture and the Japanese”. What made you start thinking about this?

Okada: I grew up listening to blues, but there was a time when I thought, "Can a Japanese person like me make a blues record?" and I found that really difficult. It wasn’t so much about whether it was possible technically, but I couldn’t find a clear reason why I, as a Japanese person, would do blues. I kept wondering how I could express blues and at what distance I should approach it. Of course, there are plenty of amazing blues players in Japan, and I personally think Takashi "Hotoke" Nagai is one of the best bluesmen out there, but that’s specifically in relation to my own experience. In that way, I also started being more conscious of the distance between myself and jazz, as it’s another form of Black culture.

━━Have you since been able to find your own sense of distance or perspective on this?

Okada: I think I’ve somewhat come to terms with it, yes. For example, when I think about where blues comes from, I don’t think there was ever such a thing as “pure blues” or “blues without any mix.” Both blues and jazz are part of Afro-descendant culture, but at the same time, they wouldn’t have existed without Western classical harmony. I think almost all music—especially post-20th century music—is the result of the mixing of various cultures. When I came to this realization, I understood that I can’t really relate to the idea of music that’s disrespectful or colonial in nature, but I do think that it’s important for people from different cultural backgrounds to engage with respect when interacting with each other. People like Ry Cooder and Herbie Mann exemplify this, and I really admire that about them.

Also, just this year, I went to an exhibition in Roppongi by Theaster Gates, a contemporary artist from Chicago, and the theme of the exhibition was “Afro-Mingei.” He’s African American but learned ceramics in Tokoname, Japan, and he finds similarities between the Black Power movement in the U.S. and Japan’s Mingei (folk art) movement. That exhibition really inspired me. It made me think, "It’s okay to call it Afro-Mingei" (laughs). Of course, Theaster also touched on the imperialistic aspects of the Mingei movement, but his work made me reflect on the importance of learning from the past, re-examining it, and using it to move forward, especially in such difficult times as today.

━━I see, the distance and respect for other cultures that you’ve developed are certainly reflected in your recent approach to jazz. Additionally, you've listened to such a vast and diverse range of music. For instance, as you mentioned earlier with Marcel Mule, bringing in names like Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou and Marion Brown, it’s fascinating how you effortlessly bridge fields and time periods, with music linking both vertically and horizontally. Personally, I also find that these kinds of musical experiences are a vital part of my own journey, so I always encourage people who love music to listen to as many different kinds of music as possible, without any boundaries.

Okada: My record life revolves around the basic idea that when I come across a fresh record that makes me think, "Wow, I've never heard anything like this before," I end up asking myself, "Maybe someone in the past did something similar," and I start searching through older records. For example, when I listened to Notes With Attachments (2021) by Pino Palladino and Blake Mills, I was amazed at how they reinterpreted Afro-funk in such a fresh way, and from there I started tracing the roots of that sound, wondering if anyone had done something similar in the past, and I ended up rediscovering Ry Cooder. The things he is doing are different from what Pino and Blake are doing, but when I think about how he was probably exploring similar ideas, I can listen to it with a new perspective. Lately, I’ve been listening to a lot of Blue Note as well, and when I re-engage with classic jazz after exploring artists like Ras G, Jeff Parker, and Makaya McCraven, I find new discoveries and connections all over again.

━━The way you approach music in such a systematic and exploratory manner is something that has definitely diminished, especially after the rise of streaming services. The joy of expanding one's musical horizons like that is something we should really try to share more. This is actually a topic I’d love to dive deeper into, but since it strays too far from the main discussion, let’s return to talking about records.

━━First, can you tell us about how you first encountered records?

Okada: When I was in middle school, I was helping my father and aunt clean out the barn at my father’s family home in Mie, and we came across some old records and a record player they used to listen to. The needle was worn out, but the player still worked and made sound. I think the first records I heard on that player were T. Rex and Takuro Yoshida, and that was my first experience of hearing music played through a record player with a needle.

━━At that time, were you already listening to music on CDs or other formats?

Okada: Yes, I was. I started playing guitar in 5th grade, so I had been listening to music for a while, and by that time, I had already started collecting CDs. In high school, my parents gave me a train and bus pass, but I would walk the 20-minute bus route to school every day to save money on the pass, and then I’d buy a lot of cheap CDs at Disk Union on my way back home (laughs).

━━Did you feel a special connection the first time you encountered records?

Okada: Yes, I definitely did. For some reason, I’ve always been drawn to older things since I was a kid. My first big obsession was cars—I was in kindergarten, but I was completely captivated by car encyclopedias and out-of-print catalogs of classic cars that older guys would typically read (laughs). I think it was the shapes and color palettes of vintage cars that fascinated me.

Naturally, as a kid, I also liked trains. But even with trains, I preferred older models. I grew up in Fussa, Tokyo, where the JR Ōme Line still had the legendary 103 Series commuter trains running, just barely. I remember around the end of elementary school, when they announced a farewell run for that train, my friends and I went to ride it one last time.

━━It’s pretty unusual to be into old things from such a young age, isn’t it?

Okada: Yeah, I’ve been told that since kindergarten (laughs). Even after becoming a musician, people still say the same thing. For some reason, older things just feel more natural to me. In high school and college, for example, I absolutely refused to use mechanical pencils—I only ever used regular pencils (laughs). I even carried a pencil sharpener to school with me (laughs).

That kind of mindset is probably why, if records were an option, I naturally gravitated toward listening to music on vinyl instead of CDs. During my last summer break in high school, I brought back a record player from my father’s family home. But since they were in Kansai region (western Japan), the player didn’t work at the correct speed in Tokyo (Kanto region) due to the frequency difference between regions (60Hz in Kansai vs. 50Hz in Kanto).

At the time, I was preparing for college entrance exams, so I decided not to mess with the record player while studying (laughs). After my exams were over, I fixed the player and started buying records.

━━Do you remember the first records you bought at that time?

Okada: I remember it vividly. I bought three records at Mezurashiya: Late for the Sky by Jackson Browne, BAND WAGON by Shigeru Suzuki, and I think a live album by Poco.

━━That’s quite a West Coast-heavy selection for a high school senior in the 2000s.

Okada: True. When I was in 5th grade, I got really into Jesse Ed Davis and Mike Bloomfield, so I’ve been listening to that kind of old-school rock ever since.

━━You were into Jesse Ed Davis in 5th grade? That’s not exactly typical for an elementary schooler. How did you get into that?

Okada: My dad was part of the folk generation, so there was an old acoustic guitar stashed in the closet. I pulled it out and started playing it. When my dad saw that I could actually play, he found it amusing and decided to buy me a copy of Guitar Magazine when I was in 5th grade. Coincidentally, that issue was a special on slide guitar. It featured players like Duane Allman, Jesse Ed Davis, and Mike Bloomfield, and it came with sheet music. So, I decided to start practicing using that. But I didn’t have any of the original recordings at hand, so I had to choose where to begin. In the score for Mike Bloomfield, there was a note that the phrase was from Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited. It looked like the simplest piece with the fewest notes, so I started there. Next, I moved on to Jesse Ed Davis because his score also seemed manageable. There was a transcription of his playing on John Lennon’s “Stand by Me” in the magazine, and as it happened, my mom had a CD with that track. That’s how I first discovered Jesse Ed Davis, and from there, I just kept diving deeper.

━━I see—you were innocently engaging with some incredibly tasteful music. Do you think growing up in Fussa played a big role in that?

Okada: Not really. I didn’t meet the “bad adults” of Fussa until I got to high school (laughs). My parents weren’t connected to the U.S. military base or anything like that either (Fussa is a town in suburban Tokyo known for hosting US Yokota Air Base). That said, in middle school, I did have a few friends who were really into music. One of them loved CSN&Y’s Déjà Vu. His parents ran a translation office and would sometimes travel to the U.S. for work. He also played guitar, and we hung out a lot. So, I think I was just lucky to have friends like that around me by chance.

━━Once you discovered records, did you continue buying both CDs and records?

Okada: No, I pretty much switched to buying only records. One reason was that back then, used records were cheaper than new CDs. But more than that, I realized from reading music blogs online that there was a much larger pool of music on vinyl that I didn’t know about compared to CDs. That discovery process was exciting. Older music that gets reissued on CD is usually already critically acclaimed, which is why it’s reissued in the first place. But finding out how much music had slipped through the cracks was incredibly thrilling. These days, if it’s something from the ’90s that only exists on CD, I’ll buy the CD as well.

━━You seem quite knowledgeable about out-of-print records and label details. When did you start getting into that world?

Okada: It’s been that way since I was a kid. Once I get into something, I tend to dive deep and really obsess over the details. For example, with cars, I loved learning about minor design changes, like how tail lights became more angular after a facelift or how a rounded design evolved. That same mindset carried over to records. I naturally started noticing things like, “Oh, this label has a JASRAC logo, so it’s not an original pressing.” It’s completely useless knowledge for everyday life (laughs).

━━Hey now, there are record store staffs who make their living with exactly that knowledge, and one is sitting right in front of you (laughs).

Okada: My apologies! (laughs) But thanks to that knowledge, I get to take part in cool record-related projects like this, so I guess it turned out to be pretty useful after all (laughs).

━━Did someone teach you how to identify labels, or did you figure it out on your own?

Okada: In college, I formed the band Mori wa Ikiteiru with some friends, and they were also into that kind of thing. We’d often chat about records and say things like, “This isn’t an original pressing.” But honestly, none of us had much money, so we couldn’t afford expensive original pressings anyway, and we weren’t super particular about it at the time.

That said, after graduating college, I worked for a few years at a record store in Kichijoji, and that was a big learning experience for me. The store manager was incredibly strict—I’d often get scolded and end up pricing records while holding back tears (laughs). I wanted to try working at a record store at least once, but I had no idea it would be such a tough job.

━━I think it might have just been that particular store (laughs).

Okada: (laughs). But that manager was incredibly passionate, and since there was so much I didn’t know, I ended up learning a lot from him. Every day, I’d have to select listening samples for tracks to upload to the store’s website, but he’d often yell, “Okada-kun, this isn’t the right section!” He’d get pretty serious about it. While I’d be on the verge of tears, deep down I’d still think, “No, this section is definitely better.” (laughs). Looking back now, I understand what the manager was trying to achieve—he wanted to choose sections that would catch the attention of DJs. At the time, I was just a music-loving listener, so my sense of what to highlight was completely different. I couldn’t understand why they’d pick something like a drum break, and I’d think, “Why would you choose this?” But sure enough, that’s what would sell the records. That’s when I really started to develop an understanding of the “DJ’s ear.” It was an intense but valuable experience that taught me a lot.

━━How often do you visit record shops these days?

Okada: Back in college, I used to go every single day, but the frequency has definitely dropped since then. That said, I’m probably still buying records at a pace of more than one per day on average… I still live in the suburbs of Tokyo, and one reason I don’t move closer to the city is because I’d probably go broke if I lived too close to all the record shops (laughs). One perk of being a musician is that touring takes me to different places, and many of my gigs are in areas like Shibuya or Shinjuku. Whenever that’s the case, I’ll slip out after rehearsals and say, “I’m just going to do a little shopping.” (laughs). I always visit record shops when I’m on tour. In fact, the first thing I do after arriving somewhere isn’t to search for my hotel—it’s to look for used record stores near the venue (laughs).

━━It seems like you’re pretty savvy about using the internet for record hunting as well.

Okada: Definitely. I’m part of the generation that grew up with the internet, so online auctions and marketplace apps are indispensable tools for me. Sometimes you can stumble across records for much less than their usual market price, so I make it a point to patrol for about 30 minutes before going to bed (laughs). I also have alerts set up for my want list. There was even a time when the auction for a record I really wanted overlapped with a live performance. I secretly checked my phone during the show and managed to win the bid (laughs). I won’t say whose show it was, though—I don’t want to get in trouble (laughs).

━━How many records do you currently own?

Okada: I haven’t counted precisely, but when I moved about three years ago, I realized I had around 3,000 to 4,000 records. Considering I’ve kept up a pace of buying one record a day since then… it’s probably more now. That said, I try to sell some while buying new ones to avoid taking up too much space—mostly to keep my wife from getting mad at me (laughs).

━━How do you organize your record collection?

Okada: I keep my “first-string” records in the living room, but the rest are stored in a spare room. I swap them in and out depending on what I feel like listening to. I divide them into general categories like rock/pop, singer-songwriters, soul, jazz, experimental, classical, and world music—kind of like a typical record store setup. For the larger categories, I roughly organize them alphabetically. For smaller sections, I sort them by mood or however makes sense to me personally. During the pandemic, not being able to visit record shops was really tough, so I bought one of those vertical “crate-style” racks as a way to cope. I use it as my NEW ARRIVAL shelf for recent favorites (laughs). Oh, and I’m in the no-outer-sleeve camp. While it does mean the jackets can get scuffed, I believe it helps with ventilation, so I stick to that.

━━We've interviewed 7 people for this series so far, and you're actually the first one to organize their shelves alphabetically. Finally, someone who does it! (laughs)

Okada: Really? How do others even find their records then? (laughs) Taniguchi (Yu Taniguchi, the keyboardist from Mori wa Ikiteiru) once told me about visiting Keiichi Sokabe’s house. Apparently, Sokabe-san wanted to play a certain record but disappeared into another room to look for it—and didn’t come back for an hour (laughs).

━━Was that the UK original pressing of The Byrds? Sokabe-san was actually our first guest for this interview series, and he mentioned that exact story (laughs). He said he spent an hour searching but couldn’t find it, which frustrated him so much that he decided to start organizing his collection properly after that (laughs).

Okada: That must be the same story (laughs).

>>> WHAT’S IN YOUR CART? #001 Keiichi Sokabe

━━Do you have a preference for original pressings?

Okada: Ideally, I want the original pressing from the label’s home country. That said, I’ve been collecting Blue Note records this year, but there’s no way I can afford to drop ¥500,000 on a single original pressing. So, I’ve set some personal rules—like for 1950s and ’60s Blue Note records, I’ll consider anything up to the blue-and-white Liberty label (left image) acceptable. The later designs are too different. I only go for the blue-label "Division of Liberty" pressings (right image) if there’s no other choice (laughs).

If I’m particularly attached to a record, I definitely prefer to have the original pressing. One memory that stands out is with Karen Dalton’s first album (It's So Hard to Tell Who's Going to Love You the Best). I originally bought a reissue new, but I’d been hunting for an original pressing for years. In 2015, Disk Union had a year-end sale, and I found one for about ¥15,000, with an extra 20–30% discount on top of that. At the time, I wasn’t exactly flush with cash—buying it meant I’d barely make it through the New Year. But I figured I’d have a warm heart, if not a warm wallet, so I went for it.

Also, I don’t care about jacket condition at all. In fact, I might even prefer ones that are a bit worn. They’re usually cheaper, and something about a jacket with ring wear just feels more “authentically vinyl.” Super pristine original pressings stress me out because I’d have to handle them so carefully. For Japanese pressings, I don’t care about having the obi either. I don’t trust myself to preserve the obi intact for future generations (laughs). So, I actively seek out obi-less copies.

━━What’s currently at the top of your record want list?

Okada: It would have to be the “mostly” original stereo version of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme I mentioned earlier. Of course, you can get almost any record if you’re willing to pay the price, but I’m the type who’d rather take my time searching for one that’s in rougher condition but priced lower than market value. I could spend years waiting to find just the right deal. That said, looking at how record prices have been trending lately, it does feel like now is always the cheapest time to buy...

Another one near the top would be the Joe Henderson album I chose today. My musical tastes shift constantly, but this year, starting with my Ras G phase, I’ve really been in a jazz mood.

━━What makes a “good record shop” in your opinion?

Okada: Hmm, that’s a tough one. For me personally, visiting large stores with a massive selection of records and digging through them on my own, without guidance, was a big part of my learning experience. So in that sense, a shop with a sheer volume of records can definitely qualify as a “good shop.”

On the other hand, smaller, more personal shops with a sense of community have their own unique appeal. Back when I was a student, I was so persistent about visiting stores daily that the staff started to recognize me. That naturally led to conversations like, “I’m looking for something like this—do you have any recommendations?” I learned a lot from those interactions with the staff, and I even exchanged information with other customers I met by chance in the shop. Those experiences have become an integral part of my life.

━━Do you have a favorite record shop outside of Tokyo?

Okada: That would be SHE Ye, Ye Records in Niigata. I’ve been a regular customer for years, even through their online store. Their selection of obscure records is incredible—it feels like a shop built entirely on items that would normally be relegated to the “OTHERS” section in most stores. It’s a uniquely evolved record shop that Japan can truly be proud of.